Gardens, gardening and horticulture are neglected aspects of Birmingham’s eighteenth-century social and cultural history; the town is more often celebrated for taking the products of nature and turning them into the products of the Industrial Revolution than it is for nurturing the art of gardening endeavour. Yet in a period when gardening underwent its own revolution, Birmingham was a centre of horticultural enterprise, gardening activity and botanical knowledge. My aim in uncovering Birmingham’s horticultural capital is to expose aspects of the town’s history beyond its manufacturing nature and to cultivate new perceptions of the town during the long eighteenth-century.

One of the areas of interest that I have developed through my engagement with the CPHC is the intersection of garden history and printing history and culture. As more nurseries opened during the eighteenth century, nurserymen adopted the medium of print to cultivate a market and to establish themselves as part of the commercial topography of urban centres. The printed plant list and nursery catalogue were not just lists of plants for sale, they were also vehicles for the circulation of new knowledge. In the eighteenth century, nurserymen began to adopt the taxonomical system devised by the scientist Carl Linneaus to name and order the plants in their catalogues thus disseminating his scientific system to a wider audience. Examination of nursery catalogues also illustrates the global nature of plant introductions, laying bare the way in which the ingredients of a landscape that came to be adopted as entirely English arrived almost entirely from elsewhere in the world.

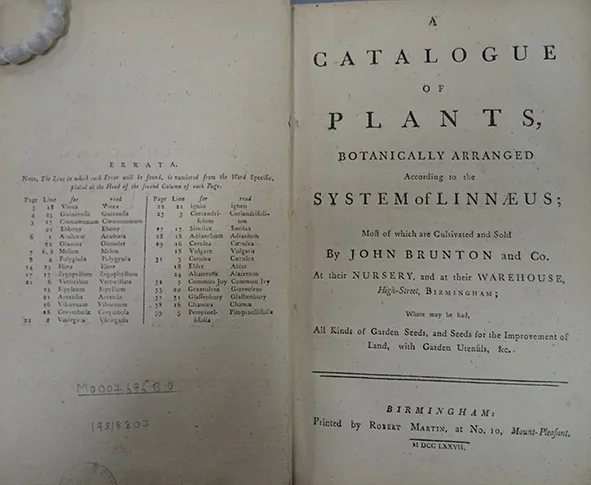

Examining a number of eighteenth-century nursery catalogues in the Joseph Banks collection at the British Library has allowed me to better consider the place of the Birmingham nursery business of Brunton & Forbes, established in the High Street from 1774. Comparing their 1777 catalogue (printed in Birmingham using the printer John Baskerville’s types) with others from the London firms of Grimwood (1783), Luker and Smith (1783) and Gordon, Dermer and Thornton (c. 1780), for example, firmly places them amongst the élite nurseries who invested in the printed materials that became part of a polite consumer culture in the eighteenth century.

As the commercial nursery business grew during the eighteenth century so too did the business of printing and Birmingham became an important provincial centre. My work on nursery catalogues has led me to consider the partnership of plants and print and future research will explore the extent to which Birmingham may have been a publisher of horticultural and botanical literature.

22 November 2017

Elaine Mitchell, Doctoral Researcher, University of Birmingham

@elaineamitchell

Image: Title page of A Catalogue of Plants Botanically Arranged According to the System of Linnaeus published in Birmingham by Robert Martin in 1777 using John Baskerville’s types (Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham).